Navajo Indians Help Explain Ethereum / Classic Replay Attacks

2016/10/11 Christian Seberino

I will explain replay attacks in general and how to protect yourself. I will give specifics regarding the Ethereum and Ethereum Classic replay attacks.

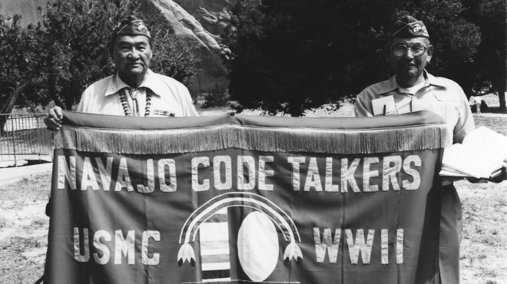

Navajo Code Talkers

Replay attacks are general attacks that are not even limited to computers. Here is an example involving foreign languages. During World War 2, bilingual Navajo soldiers secured communications by transmitting messages in the Navajo language. If no extra precautions were taken, imagine the chaos that could ensure by simply repeating previously intercepted radio messages to random units. You would not know what you were transmitting, but, you could conceivably send unsuspecting American soldiers messages such as “MOVE 1 MILE WEST NOW” or even “ATTACK NOW”. Notice this takes little effort. It does not even require deciphering the foreign language!

Remote Controlled House

Here is an example of a replay attack involving computers. Imagine you decide to make your house remotely controllable with text commands while you are on travel. You decide to take extreme measures and only send commands over the Internet that have been SHA-256 hashed 100 times. The following Python code will encrypt your commands thusly:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import hashlib

NUM_OF_HASHES = 100

encrypted_text = input("What is the house command? ")

for i in range(NUM_OF_HASHES):

encrypted_text = hashlib.sha256(encrypted_text.encode()).hexdigest()

print(encrypted_text)

You can run the script yourself to see that for the command “WATER THE LAWN NOW”, the encrypted text to send will be:

0e7a9b2e305988a09ca6431dcc2ccff50db2e0922e43d90c3950f1b16842a82f

For the command “INCREASE THE TEMPERATURE 5 DEGREES”, the encrypted text will be:

66e14d7c75f8ef72a74d99d6690169aff310b7c6cc0d79ad09a945e8c926cf17

If someone listens in on the transmission, all they would see is unintelligible bits. Imagine the mischief someone could cause by resending the above two encrypted commands to your house every ten minutes nonstop. This is another example of an attack that is easily carried out. The attack is even effective against (apparently) strong encryption!

Protecting Against Replay Attacks

The problem with the aforementioned scenarios is that the same messages always have the same corresponding encoded text. This method, with regards to encryption, is referred to as Electronic Codebook (ECB) mode. What is needed is some variability in all messages. For example, imagine if the date and time were added to messages with the understanding that messages were to be ignored after an agreed upon expiry. That would prevent replay attacks. Another simple solution is to add a unique number to every message. Unique message numbers are referred to as nonces.

What About Ethereum & Ethereum Classic?

Ethereum (ETH) and Ethereum Classic (ETC) do have protection against replay attacks. All transactions on both systems have nonces! If you send me some ETH tokens from your ETH account, I cannot replay that transaction (“double spend”) on the ETH system to get more; likewise for the ETC system. However, both systems are sometimes vulnerable to replay attacks involving the resending of transactions between systems. The reason for this is that the uniqueness of corresponding nonces between the two systems is not required.

The replay attack transaction

0x87f8a62d4f04776701e95672b85838c818ceff3102d72be9377ede77ed59f83b (minus the digital signature) on ETH block 1,920,100:

| FIELD | VALUE |

|---|---|

| Nonce | 115255 |

| Sending Address | 0x4bb96091ee9d802ed039c4d1a5f6216f90f81b01 |

| Receiving Address | 0x5d438e155d0b38c568496c411a4bcc1dcf45632a |

| Ether Sending | 5.008931333047880161 |

| Data Sending | (None) |

| Max Gas Units Can Use | 90000 |

| Price Per Gas Unit In Ether | 0.000000021786783329 |

The same replay attack transaction

0x87f8a62d4f04776701e95672b85838c818ceff3102d72be9377ede77ed59f83b (minus the digital signature) on ETC block 1,920,021:

| FIELD | VALUE |

|---|---|

| Nonce | 115255 |

| Sending Address | 0x4bb96091ee9d802ed039c4d1a5f6216f90f81b01 |

| Receiving Address | 0x5d438e155d0b38c568496c411a4bcc1dcf45632a |

| Ether Sending | 5.008931333047880161 |

| Data Sending | (None) |

| Max Gas Units Can Use | 90000 |

| Price Per Gas Unit In Ether | 0.000000021786783329 |

What specific funds are at risk? Funds associated with the same address on both blockchains are at risk. Therefore, this pertains to all funds existing before the ETH hard fork that now exist on both systems. Notice this vulnerability does not pertain to the DAO related funds with modified histories. This is because these funds do not exist at the same addresses on both blockchains.

Solutions Part One

The easiest solution is to just send your funds to an exchange that promises to secure your funds for you. If you want to protect your funds yourself, you need to add variability between the funds on both blockchains. Since nonces are not providing that, another method is needed. The easiest way to add variability is to move funds to different addresses on each blockchain. Using two wallets, one for each system, send the funds from the same addresses to different addresses on each system.

Solutions Part Two

Perceptive readers may wonder whether the transactions that send funds to different addresses on each blockchain are themselves vulnerable to replay attacks. There is a possibility that your attempt to add variability in the addresses fails. But, that would just mean that your funds end up on the same new addresses on both systems controlled by you! You could simply keep trying until you succeed in sending your funds to different addresses on each blockchain.

Solutions Part Three

Perceptive readers may also wonder whether an aggressive attacker could make it impossible to successfully move funds as required to protect them. Assume all transactions are instantly copied to both systems. The countermeasure for this situation relies on the fact that there is uncertainty in the time required to process (“mine”) new transactions on blockchains that use proof of work information. You could broadcast the two transactions, meant for different blockchains, to one blockchain. Why would this thwart every replay attack? Remember that the ETH and ETC systems both have replay attack protection with regards to multiple transactions on the same blockchain. One of the transactions should be accepted, and one rejected, on each blockchain. No one can predict which of the two transactions will be accepted on either blockchain without also compromising mining nodes. It may take multiple attempts, but, eventually funds will end up at different addresses on each system.

Solutions Part Four

Perceptive readers may also wonder whether new funds, sent to old addresses that previously held funds on both systems, are also vulnerable to replay attacks. In some cases the answer is yes. The simplest advice regarding that concern is to just avoid doing that. In other words, do not reuse vulnerable addresses. Arrange it so that no funds are ever sent to those addresses again. If someone nevertheless insists on reusing addresses that exist on both chains, more work is required to secure future funds sent to those addresses.

Parting Thoughts

Everyone must be vigilant about protecting their cryptocurrency. Fortunately, there are effective tools and techniques that provide adequate safeguards. The dangers cannot be ignored. As an old Navajo proverb says:

“Coyote is always out there waiting, and Coyote is always hungry.”

Feedback

You can contact me by clicking any of these icons:

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Nick Johnson and Timon Rapp for their help. I would also like to thank IOHK (Input Output Hong Kong) for funding this effort.

License

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 4.0 International License.